Good Death, Bad Design

When the systems around dying are clinical, alienating, or inaccessible.

Most people don’t fear death in the abstract as much as they fear how we let them die — hooked to machines they didn’t choose, away from people they love and inside processes they can’t afford or understand.

It’s a complete design failure.

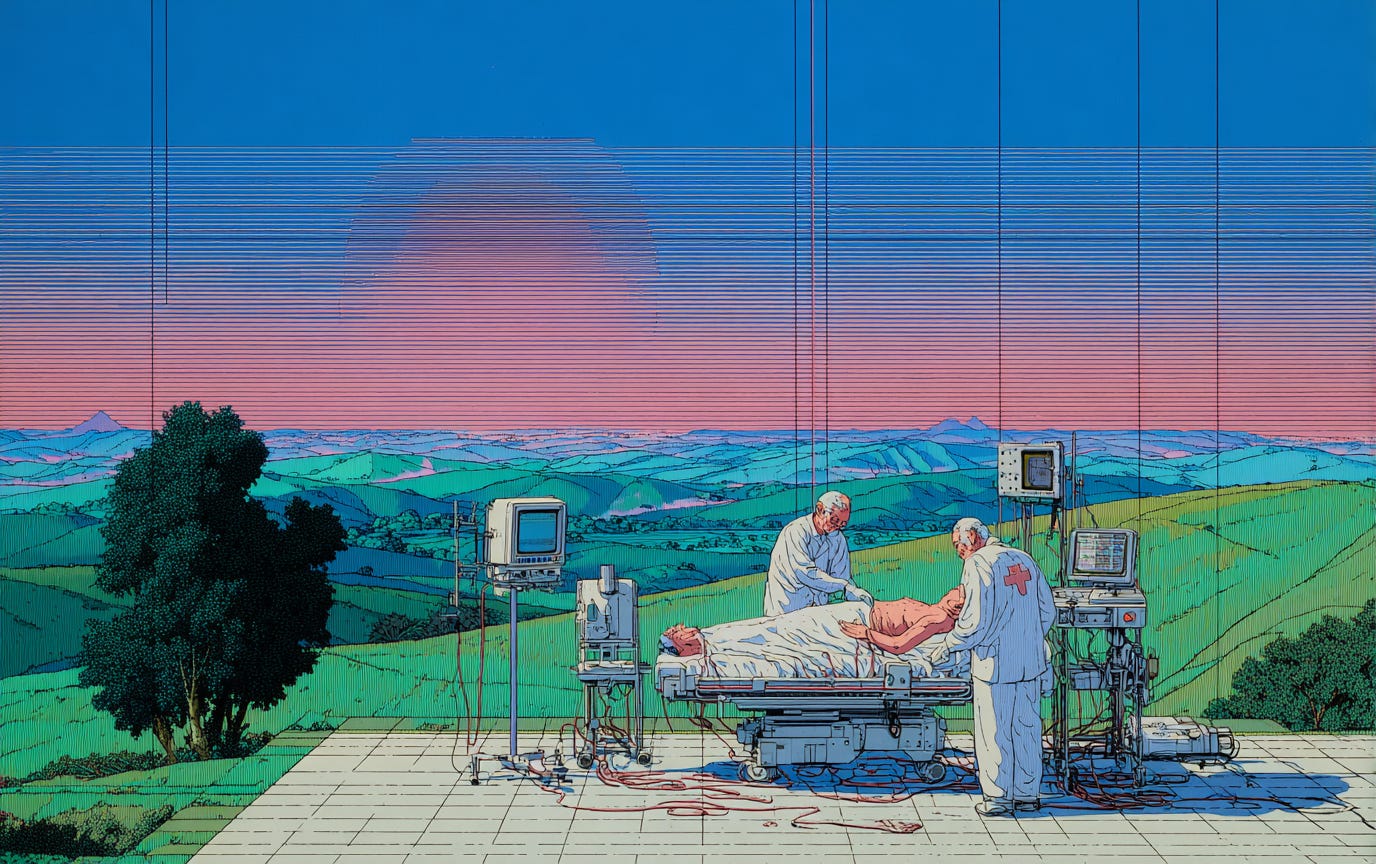

Clinical: when medicine turns dying into a technical problem, not a human one.

Hospitals are extraordinary at fixing bodies, but clumsy at closing lives. The Lancet Commission argues that modern healthcare often treats death as failure, leading to over treatment and late or absent palliative care, despite evidence that palliative approaches improve quality of life and lower costs.

The ICU is where this tension is most visible. About a fifth of ICU admissions end in death; family experience hinges less on gadgets and more on communication, inclusion, and setting. Families report better outcomes when clinicians explain options and bring them into decisions; and when they lack this communication, it intensifies their distress.

Alienating: when rituals, rules, and interfaces push people out.

Visitor bans during COVID exposed how brittle our end-of-life rituals are when policy trumps presence. Studies describe profound, lasting harms: families unable to say goodbye, complicated grief, and clinicians bearing moral injury trying to bridge the gap over FaceTime.

Alienation also hides in digital remains. Most of us leave sprawling accounts; a few platforms allow planning (Google’s Inactive Account Manager; Apple and Meta’s legacy contacts), but the experiences are inconsistent, heavy, and easy to ignore until it’s too late — leaving next-of-kin to navigate policies while grieving.

Inaccessible: when dying costs more than living.

The WHO estimates only about 14% of people worldwide who need palliative care actually receive it—a stark access gap that leaves millions without pain relief or support.

In the U.S., the median cost of a funeral with burial is now $8,300 (cremation median $6,280), pushing families toward cheaper, thinner rites. In the UK, the cost of dying (funeral + professional fees + send-off) has hit record highs, with basic funerals around £4,141–£4,285 and more families turning to crowdfunding.

Why this is a problem for design (not just policy or ethics).

Design decides defaults, rooms, screens, and scripts. It decides whether the “standard path” is escalation or comfort; whether a space has a chair for your sister, a dimmer for the lights, a door that closes; whether your accounts vanish, memorialize, or metastasize. As those decisions and designs become an invisible, they define the conditions of our dying for the better.

What ‘better’ tends to look like (in practice, not perfection).

Earlier palliative conversations integrated into routine care, not a last-minute referral. (This is exactly what the Lancet Commission calls for.)

Spaces that support presence—quiet rooms, fewer alarms, policies that presume family at the bedside when safe to do so.

Clear, humane digital off-ramps—legacy contacts set up when you set your passcode; inactive-account nudges that use plain language; options you can change in two taps.

Transparent, affordable funerals—itemized prices, community options, and culturally flexible rites that don’t punish poverty.

None of this is grand theory. It’s small, cumulative choices that add up to whether the end is navigable.

We don’t need perfect deaths.

We need good enough endings in systems that remember what they’re for: easing pain, protecting presence, and leaving families with fewer regrets than receipts. That’s the work. And it’s absolutely a design job.